Many industries use pressurised rooms to stop cross-contamination between one area of a building and another. For example, semiconductor makers use positive pressure rooms (PPR) to ensure their integrated chips are free of contaminants in the air. Hospitals and clinics employ negative pressure rooms (NPR) to contain the spread of infectious diseases. The difference between positive vs negative pressure rooms is mostly one of pressure differential and air flow. Both approaches use air pressure differentials to control ventilation and contamination.

Pressure Differential

Anyone who’s ever let go of an un-knotted balloon has witnessed the propensity of air to move from a higher pressure area to a lower one. The bigger the pressure differential, the faster the balloon will fly around the room. Building managers use HVAC equipment, fans and ventilation systems to control this natural propensity of air to escape—to keep the “balloon” knotted as it were.

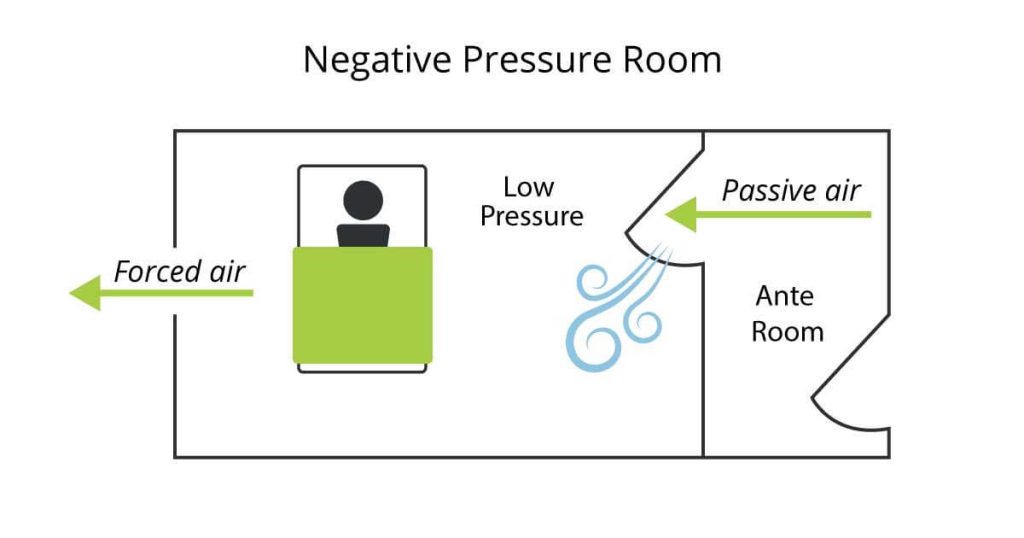

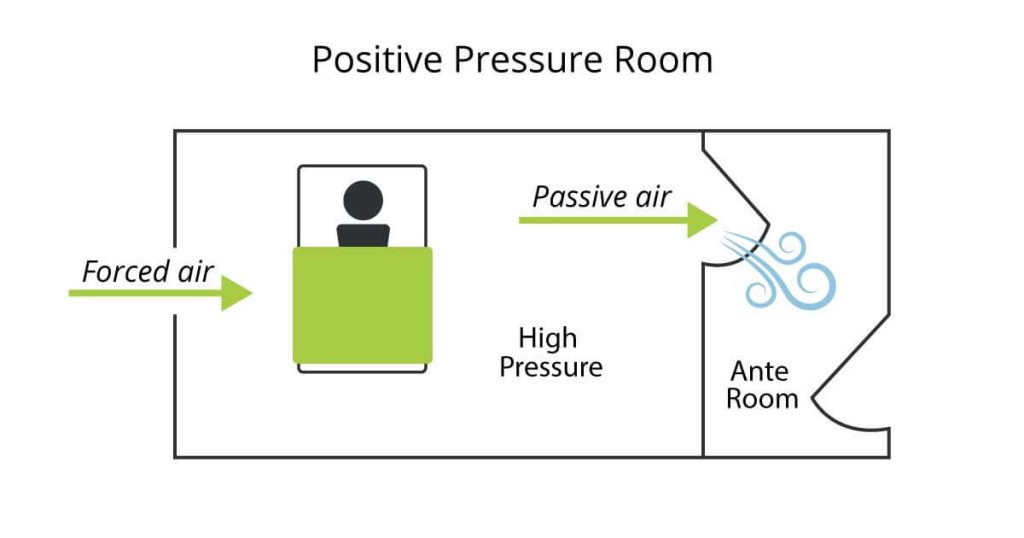

The natural movement of air without the aid of mechanical equipment like a fan is called “passive” air flow, and techs use passive air flow to keep debris and contaminants from entering or exiting a room. If done correctly, the result is a stable environment with lower or higher air pressure than the surrounding area.

What’s a Negative Pressure Room?

To create a NPR, HVAC professionals must move air out at a faster rate than it comes in. That is, a negative quantity of air maintained. The purpose is to control the direction of passive airflow. When someone opens the door of an NPR, negative pressure draws passive air inside, forming a barrier against the escape of pathogens or dust. Interior air then moves through a filtration system to remove contaminants before safely exiting the pressurised environment.

What’s a Positive Pressure Room?

Positive pressure rooms maintain a higher air pressure inside than the surrounding environment. Air escapes the room without letting in outside contaminated air. PPRs exist within surgical theatres and in vitro clinics where contamination is possible. PPR hospital rooms often house immunocompromised patients susceptible to infection or disease. Because PPRs form barriers to outside spaces, their HVAC systems must filter out any contaminants from the interior air while ensuring optimal pressure and safe air quality.

Air Tightness

Pressure room designers try to keep rooms as air tight as possible, but some leakage occurs through gaps in doors, windows and electrical outlets. Designers often outfit NPRs with ante rooms to minimise leakage. These entryways are also safe areas for removing PPE or as a failsafe against pressure loss. Airtightness is also a cost issue. The more leakage, the more energy required to maintain a room’s negative or positive pressure.

Air Comfort

Like any conditioned environment, pressurised rooms must also maintain humidity and air temperature to ensure comfort and safety. Air quality is particularly important for medical facilities, since suboptimal humidity levels can contribute to illness. To aid air quality, HVAC technicians design HVAC systems to include specific numbers of air changes per hour (ACH) based on the size of the room. ACH is a measure of how often air within a space is replaced every hour and is essential to combating contaminated, stale and unhealthy air.

Testing and Monitoring

Smoke tests are a common way to test the effectiveness of a pressurised room. They’re cheap and easy to administer, but aren’t continuous or highly accurate. During a smoke test, technicians create puffs of smoke next to known intakes like registers or under doorways. If the smoke flows inside or outside, then a pressure differential exists. The smoke just needs to move in the right direction. Electronic pressure monitors offer continuous, accurate monitoring, but they’re expensive to purchase and install. Still, accurate testing and consistent monitoring is the best way to maintain the effectiveness of a pressurised room. Inadequate or infrequent testing puts patients and others at risk.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has extended the use of pressurised rooms to combat the disease. The idea has extended beyond the hospital room to include waiting rooms, triage, bathrooms and other areas that could contain contaminants or susceptible people.

While pressurised rooms are helpful for health care workers, patients and staff, they also present challenges to HVAC techs and facility managers. Expanding the number and size of pressurised areas in any building means paying more attention to resulting issues like high humidity levels, sticky entryways, mold growth, and increased energy costs. These are new challenges FMs and engineers will need to address as the built environment evolves to meet social change.